A data-driven approach to maximizing emotional wellbeing

Introduction

I graduated college in 2020, a few months after the pandemic hit, from a renowned university attended largely by driven, ambitious, high-achieving students. For me and my friends, transitioning to post-college life would have been difficult at the best of times, since our lifelong pursuit of academic excellence would no longer shape our daily lives. Graduating in the midst of global turmoil, economic uncertainty, and a documented nadir of mental and emotional health among American adults, was even less ideal.

What differentiates adulthood from childhood is the need to constantly make decisions. Big, grand decisions–which job to take, which city to move to, when and whether to get married–and small, everyday decisions–whether to wake up an hour early to go to the gym, what food to eat, and how much, and at what times, whether to go to your friend’s birthday party or stay inside watching Netflix. Of course, these decisions exist for children and college students as well. But so much of life is outside of one’s control before adulthood; my childhood self never had the sense that it was my responsibility, and mine alone, to make the right decisions to live a happy life. After all, there was a safety net of parents, teachers, guidance counselors, babysitters, and institutions expressly designed to make decisions for me.

With graduation, however, came both freedom and oppressive responsibility. There was no one left to take care of us or shepherd us toward a happy future. We determined our own destinies–which meant that if we were unhappy with those destinies, there was no one to swoop in and rescue us but ourselves. With increased freedom of choice came an increased obligation to choose, and increased self-scrutiny about the quality of each decision.

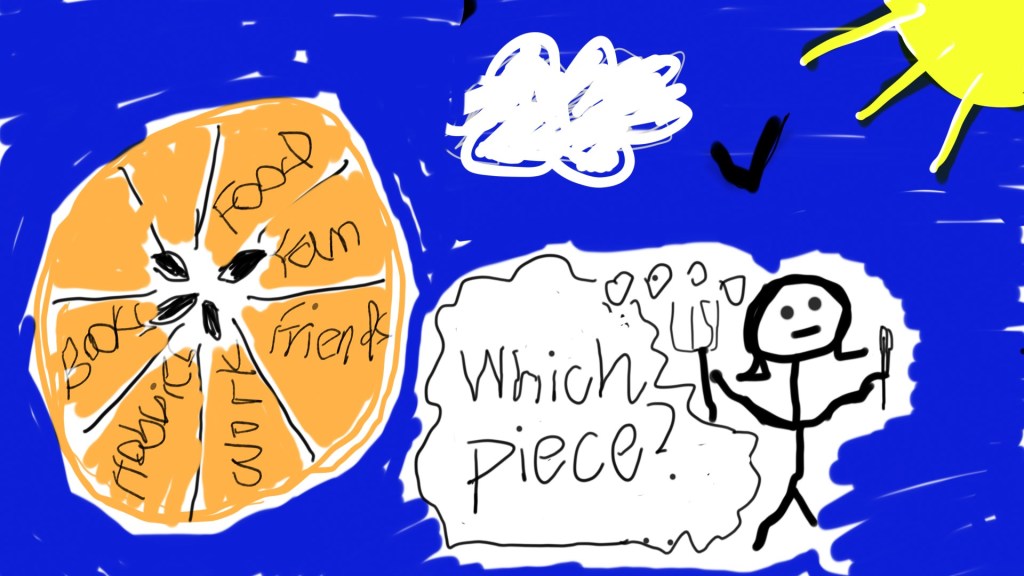

As I supported many of my friends through their quarter-life crises, and underwent a few of my own, one thing became overwhelmingly clear: none of us had the slightest clue what really made us happy. We would talk in endless circles about the various subsections of our lives–our jobs, our relationships, our habits–and agonize just as endlessly about the choices to make within those subsections. But all too often, the choices we made had no impact, or even had a negative impact, on our feelings of happiness.

Why was that? Why did everyone jump immediately into making big, significant choices before having any real understanding of even the categories of choices that actually mattered to their emotional wellbeing? Why did we lack fundamental self-awareness about something as crucial as what brought us joy?

To put it more broadly: how should we prioritize the various controllable categories of our lives, and make choices within those categories that effectively maximized our happiness?

In an effort to answer these questions, I embarked on a year-long experiment that I called the Happiness Regression. Armed with two undergraduate business courses in data analytics, a bright pink notebook that I’d always deemed too ugly to write in, and irrepressible existential ennui, I set out on a data-driven approach to tracking, understanding, and eventually optimizing my own happiness.

Data Collection

To understand which aspects of my life had the strongest statistical relationship to my happiness, I turned to the concept of simple linear regression. Regression is a tool in data analytics that allows researchers to build a predictive model of the relationships between several independent variables and a single dependent variable. With all the independent variables operating simultaneously and changing in different ways, a regression model can tell you how a change in any one independent variable is likely to affect the dependent variable. In my case: how a change in any of the controllable categories I identified would impact my happiness.

First, I defined the variables. The dependent variable, obviously, was happiness, which I decided to rate on a scale of 1-10, with 10 being the happiest I could imagine being, and 1 being the most miserable.

I had to spend more time thinking through the independent variables. Statistically speaking, 7-10 independent variables is the optimal number for a multivariate regression model. I tried to split my daily life into subcategories, and then select a set of those subcategories that a) I felt I had some control over, and b) I believed intuitively were linked to happiness. Allow me to caveat by saying that this list is mine and mine alone; another researcher replicating this experiment, who lives a very different life than mine, might have made different selections based on their unique circumstances. But I decided on the following categories:

- Family

- Friends

- Food

- Day job

- Night job (I work a part-time job on evenings and weekends to supplement my income)

- Hobbies

- Something I read or watched

- Exercise

At the end of every day, I rated my overall happiness on a scale of 1-10. Then, I rated each of these individual categories. For the independent variables, I used a 1-7 scale rather than a 1-10 scale to make a true neutral easier to identify: I would rate a category as a 4 if it was either not present or had no impact on my life that day (for example, a day when I did not work my night job or even think about it).

It’s important to note that what I was rating with the independent variables was not how happy they had made me that day. If I said “wow, the food I ate today was really delicious and made me really happy” and rated it a 7, my regression model wouldn’t be very meaningful; food would by definition have a strong correlation with happiness, because the independent variable I would be measuring was essentially “my happiness derived from food today” and the dependent variable would be “my overall happiness today.”

To avoid this circularity, I attempted to rate the independent variables based on their prominence in my life that day, which could skew positive or negative. To keep with our food example: if food occupied no real time or energy in my day, I would rate it a 4. If I spent a lot of time cooking a new dish, and I cooked it successfully and felt physically good after eating it, I might rate it a 6 or a 7, regardless of whether I actually enjoyed the process of preparing or consuming the food. If I spent a lot of time cooking a new dish, but I burned it and got food poisoning afterwards, I might rate it a 1 or a 2, even if I jammed out to some rocking tunes while the casserole scorched and the misadventure gave me an excuse to get takeout sushi. In essence, I was rating the directional significance of that variable in my day–how much time and energy it took up, and whether that time and energy was largely in a positive or negative direction.

Directional significance is distinct from happiness. For me personally, this might be most obvious with the “friend” variable, which I will attempt to explain using a (very hypothetical, not at all real, I have definitely not experienced this exact situation multiple times) example.

I am naturally an introvert and rarely enjoy socializing. So on a day when I decided to abandon my book and go to a friend’s birthday party, and the friend was delighted to see me, and I spent hours talking to a wide variety of new and interesting people, I might rate the “friends” category a 7: it took up significant time and energy that day, and by any objective metric it was a day of successful social interaction. However, it didn’t necessarily make me happy–I might be bored and uncomfortable throughout the party and go home feeling drained, regretting ever stepping foot outside my door. In other words, the directional significance of my interactions with my friends was different from the happiness that those interactions brought me.

To further elucidate this scoring system, I’ll narrate an example day and explain how I would rate each variable.

Anne wakes up an hour earlier than usual. She eats cereal for breakfast and does an hour of exercise, in an attempt to boost her energy levels for the work day to come. It doesn’t work, and instead she regrets losing an hour of sleep to work out.

Anne has many tasks due at work that day, and her boss has scheduled several meetings to check in on the status of various projects. She works all day, stopping briefly to eat an apple and protein bar for lunch, and successfully completes all the tasks on her to-do list.

After work, she decides to enjoy the spring weather and take a walk around the park. She listens to music while she walks and soaks in the sun, having a lovely time.

She goes out to dinner with a friend, who spends the whole time rhapsodizing endlessly about her new romantic relationship. Anne, having no real insight into this matter, does a lot of supportive nodding, and is eager to go home when dinner is done.

Anne attempts to finish writing a song she’s been working on when she gets home, since the album she is planning to release soon has yet to be completed. The songwriting session is not productive–not only does she not write any new lyrics, she in fact deletes a verse and a chorus she had written the day before.

Giving up, Anne reads a few chapters of a book she’s been greatly enjoying before going to sleep.

Ratings:

- Happiness: 3. Anne wasn’t miserable, but she was slightly cranky for most of the day and felt a general existential ennui about the quality of her career and friendships.

- Family: 4. Anne spent no time with her family, did not talk to them, and did not think about them for any meaningful length of time. They played no significant role in her day.

- Friends: 5. Despite the fact that she didn’t particularly enjoy herself, Anne did go out and socialize with a friend, and the two engaged in meaningful dialogue.

- Food: 4. Anne spent almost no time preparing or thinking about food, and no more than the average amount of time eating food. She felt no abnormal physical effects from food, whether positive or negative.

- Day job: 6. Anne didn’t enjoy her day at work per se, but it certainly took up a preponderance of her time and mental energy, and she successfully conducted several meetings and completed a long list of tasks.

- Night job: 4. Anne didn’t work her night job or think about it throughout the course of the day.

- Hobbies: 2. Anne spent a significant period of time working on a hobby (songwriting), but made negative progress on the song she was attempting to write.

- Something I read or watched: 4. Although she greatly enjoyed the hour she spent reading, she reads an average of an hour every day, and she didn’t spend more time or energy than usual thinking about what she was reading.

- Exercise: 6. Anne worked out for approximately 2 hours in addition to her standard daily activities, which is greater than her average workout time. This is a healthy choice despite not being something that brought her enjoyment.

Of course, there were many subjective elements of this data collection process. First of all, I almost always wrote down my ratings at the very end of each day, right before going to sleep. Although I made an active effort to think about my day holistically, it’s very possible that the ratings were influenced by the mood I was in at that moment (which, being very much not a night owl, was often cranky). But although that might have lowered the relative happiness scores, it lowered them all uniformly, and so shouldn’t affect the validity of my model.

Second, the scales and numbers themselves were fairly arbitrary. If I spent all Saturday with my brother Roman and we had a great time together, was the “Family” score for that day a 6 or a 7? Was it even possible to score a 7 if Roman and I were not actively winning the lottery and swimming in a hot tub full of chocolate? I acknowledged the arbitrary nature of the rating system; however, I decided that since I’d be the one doing the data collection all year, I would hopefully at least be consistently arbitrary in my evaluations.

Third, the categories themselves were a bit squishy. If I watched a football game (go Chiefs!), did I count that as a “hobby” or “something I read or watched”? But once again, I decided that as long as I made a decision and stuck with it (i.e., considered every Chiefs game I watched as “something I read or watched” rather than calling half of them a hobby), it shouldn’t adversely affect the model.

And the final nail in this experiment’s coffin of objectivity, of course, is what I was tracking in the first place: happiness. Everyone defines happiness a little bit differently. Is it a feeling of placid contentment? Is it excitement? Is it existential fulfillment, or momentary pleasure? I suspect everyone has their own, unique internal formula combining all these elements into that nebulous sensation of “happiness.” And though I may not be able to define mine precisely, I believe that I know it when I see it–or, I guess, know it when I feel it. At least, I never had any difficulty rating my own happiness level at the end of the day, subjective as that measure may have been.

I collected data in this way every single day for an entire year: January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. I never missed a single day, and I did my best not to look at the data or track any trends throughout the year.

I had three primary questions:

- What proportion of my overall happiness was attributable to the variables I tracked?

- Which categories of my life had the most significant impact on my happiness?

- Could I use my model to actually predict future happiness, and make both small and large decisions to maximize it?

Data Analysis

On January 2, 2024 (I took a day off due to a combination of fear and lethargy), I copied 365 days’ worth of data from my garish pink notebook to a Microsoft Excel worksheet. I had installed the Data Analysis package a few years ago for one of my business courses, and I had at least a hazy memory of how to perform a linear regression. Luckily, Excel does everything for you; so after a quick Google search to refresh my memory and a little clicking around, I had my results.

Here is the regression output:

I make no pretense of being a data scientist, but here’s a quick explanation of the basics of linear regression, in case you’ve been spending your time in more interesting and edifying ways than rereading your old AP Stats notes:

- The R Square value indicates the percentage of the variance in your dependent variable (i.e. the amount of change in daily happiness) that is attributable to changes in all of the independent variables.

- The coefficient of each independent variable tells you by what amount the dependent variable will change if you change that independent variable by 1. So, for example, a coefficient of 0.628 indicates that if my rating of the “family” category increased by 1, I could expect my happiness level to increase by 0.628.

- The P-value indicates which variables are “statistically significant.” Statistical significance is a tricky concept. Basically, it measures which independent variables have a strong enough correlation with the dependent variable to be meaningful in analysis. More formally, a P-value indicates the chance that the observed data would be found randomly in nature; a low P-value means that it’s unlikely that the observed relationship between a dependent and independent variable occurred by chance. Most statisticians view any P-value that is lower than 0.05 as statistically significant. As you can see, in this model, all independent variables except for “hobbies” are statistically significant.

- The intercept (-6.89) theoretically represents what my expected happiness would be if all independent variables were set to 0 (I would not be a very happy camper on this hypothetical hell day). Since the scale of all the independent variables was 1-7, however, the intercept is not meaningful to this analysis.

- When combined together, the intercept and all the independent variable coefficients can create a “formula” to predict the dependent variable, like so:

Happiness = -6.89 + 0.628(family) + 0.392(friends) + 0.199(food) + 0.622(day job) + 0.444(night job) + 0.111(hobbies) + 0.359(something I read or watched) + 0.345(exercise).

- An important assumption of linear regression is that all the independent variables are, well, independent of one another. For example, I suspected that my “family” value might have a positive correlation with my “food” value, because I often visited my family for a delicious Sunday dinner. This is called “multicollinearity,” or, to those in the know, “bad.” Luckily, there is a simple statistical test for multicollinearity that involves performing a bunch more regressions, using each independent variable as a dependent variable and calculating what’s called a variance inflation factor (VIF). After calculating the VIF of each independent variable in my model, I determined that all were under the statistical threshold for multicollinearity.

Thanks to the wizards of Microsoft, I had my regression model. Now it was time to see whether it could answer my questions.

#1: How much of my happiness is attributable to the life categories I identified?

The first thing I needed to know was whether I had even been looking at the right variables. If my goal was to maximize my own happiness, had I picked the aspects of my life that could actually help me do that?

The way to answer that question is to look at the R Square value, which, as explained above, tells us the percentage of variance in our dependent variable that is attributable to changes in all the independent variables. In this case, the R Square value of the regression model was 0.535. That means about 54% of the fluctuations in my happiness on a given day was thanks to changes in my family time, friend time, day job, night job, etc.

This R Square isn’t great. Most statisticians look for an R Square of 95% or higher before they’ll call a model predictive (although there is no defined minimum threshold, and what is considered a good R Square is highly context-dependent). But although this result isn’t ideal from a data science perspective, it is interesting. Sure, there were plenty of controllable life categories I didn’t track–both because I didn’t feel they were particularly significant in my life and because I wanted to stay in the 7-10 variable range. For example, I could have tracked romantic relationships, or the amount of money I spent on a given day (both variables I considered but ultimately did not include). But still: look at the list above and most people will agree that it represents at least most of the aspects of your life that are mostly within your control. And so this R Square value means that the aspects of your life that are most easily definable, trackable, and subject to the choices you make only account for about half of your happiness–leaving an entire 46% to the whims of uncontrollable and unpredictable events, and/or underlying mental and emotional health conditions.

Is this idea affirming or terrifying? On the one hand, of course, I’d like to think that my happiness is entirely within my control. On the other hand, it does lessen the pressure on me and my fellow at-sea twenty-somethings, freeing us from some of the oppressive responsibility we feel for optimizing our own lives. Optimize all you want–but remember that will only take you halfway.

One way to improve the R Square of this model would be to remove outliers, or days that had extremely high or extremely low happiness ratings for reasons other than the data I tracked. I kept a record in my pink notebook of significant events that happened each day, not all of which could be tied to an independent variable. I underwent a series of medical procedures, for example, that diminished my happiness significantly even though they had no bearing on the 8 independent variables I was tracking. By removing outlier days, I could very likely improve the predictive accuracy of my regression. I chose not to do this–not (exclusively) due to laziness, but because the original regression aptly answered my initial question. I wanted to know how much of my happiness was attributable to circumstances under my control. The answer? Not very much at all.

#2: What categories of my life have the most significant impact on my happiness?

Since the P-value of 7 of my 8 independent variables was lower than 0.05, all categories except hobbies were “statistically significant” in the regression, meaning they have a strong enough correlation with happiness to be useful in the model. To answer this second question, I started by re-running the regression without including hobbies, so all independent variables were statistically significant:

Then, I put the independent variables in order by size of coefficient:

- Family (0.63)

- Day job (0.62)

- Night job (0.45)

- Friends (0.40)

- Something I read or watched (0.36)

- Exercise (0.35)

- Food (0.20)

As you can see, there are some distinct groupings within this ranking of independent variables: family and day job are about tied at the top, followed by a fairly significant gap before night job, the next independent variable. Friends, something I read or watched, and exercise were all approximately tied, with food bringing up the rear.

The larger the coefficient, the greater the statistical impact on happiness that category wields. So theoretically, if I were to begin making decisions based on this model, I should prioritize the variables with the higher coefficients. This means that all other things being equal, if I am making life tradeoffs, I should devote time and energy to family and my day job more so than working out, reading, or spending time with friends.

I was not thrilled, but also not surprised, by the ordering of these independent variables. If you had asked me before the experiment began “what are the most significant aspects of your life,” family and day job would have topped the list. As much as I would love to never have a career-related existential crisis again (if, for example, I had learned it didn’t have much of an impact on my happiness), I now have data-backed evidence that the big things really do matter.

Skeptical readers might remark that all these coefficients are pretty low. The highest-impact independent variable only moves the overall happiness value by 0.63 units. But remember: happiness uses a 10-point scale, so an upward movement of 0.63 is a solid 6% happiness increase. Not too shabby–especially when you consider that for many of these independent variables, the time and energy it takes to move them from a 4 to a 5 might be very low. For the “family” variable, for example, a ten-minute phone call with my brother on my walk to work might be all it takes to bump that day’s family rating from a 5 to a 6, and then bam: I just got 6% happier.

Thinking about these coefficients more abstractly, I actually think it’s extremely important that all coefficients are relatively low. It speaks to the reality (which is not always an intuitive one) that slight improvements across an array of aspects of your life may be more effective at improving happiness rather than a large change in any one category. This is the reason not to switch careers from a librarian to a nurse anytime I’m feeling blue. Even if my day job rating consistently rose from a 4 to a 7, that would only increase my happiness by about 1.8, or 18%–an important increase, but when you consider the other important aspects of my life that may be derailed by the career shift (for example, less time to spend with family or friends, plus having to, you know, poke people with needles and stuff), probably not worth the chaos and turmoil. I believe it is human instinct to want to make big changes when we’re feeling big feelings. But this data has allowed me to calm down in moments of crisis and think about small, manageable improvements I can make to as many dimensions of my life as possible, without having to blow up and transform any one category.

#3: How could this approach be used by myself or others to predict future happiness, and make choices accordingly?

Even with a low R Square, can this model be used to predict my happiness, and can I use it as justification for life decisions and trade-offs that I make?

Well, whether or not the statisticians would say yes, I’ve already begun doing so. There have been days in 2024 when, instead of leaving work early to meet up with friends, I’ve spent more time on the clock, to improve the positive directional significance of my day job. I’ve implemented a policy whereby I spend one-on-one time with each member of my immediate family at least once a month. I’ve given up worrying about cooking long or elaborate meals, and I no longer feel guilty about not knitting enough.

I think it’s too soon to tell whether these decisions will really make a positive impact on my happiness, but I can say that I am less scared by the prospect of making those decisions than I was before. Rather than feeling completely at sea, faced with infinite choices and no knowledge of which choices to make or even which categories of choices to make, I have marginally more insight into the things that matter most in my life and the extent to which my happiness is under my control.

I absolutely see a world in which this is a usable tool for other people’s lives. For example, someone far smarter and more tech-savvy than I could create a mobile application where users could input their own custom independent variables, the app would send a push notification every evening to remind them to track the data, and users could see real-time data visualizations and regression analysis with the push of a button.

But even if someone doesn’t want to use an app, or even dedicatedly track data every single day, I believe that just taking the time to really think about what is important in our lives–think, rather than spiral-panic–will help us feel more in control of our happiness and emotional health.

Conclusion

Real, valid, hard science should transcend the personal, and be universally applicable across the population of interest (in this experiment, all mankind). My Year of Living Regressively, and the insights I generated from it, are extremely personal, and won’t apply in the exact same way (or maybe at all) to others. The experiment was subjective, arbitrary, and backed by only a beginner’s understanding of data analytics.

However, great science often starts from the personal. We conduct experiments to answer questions, and it is natural that many of our most pressing questions stem from our lived experiences. And we ourselves are often the most accessible lab rats. Barry Marshall, for example, once drank a flask of bacteria to prove a correlation between bacterial infection and ulcers (he got an ulcer almost immediately, recovered, and eventually won a Nobel Prize for his efforts).

Barry Marshall I am not, but I retain hope that my yearlong journey might be interesting to someone other than myself, and perhaps prompt others to think a little more deeply about the directional significance of the controllable categories of their lives.

This experiment was highly subjective, but it was also interesting, and useful, and made me feel slightly more capable of being a happy and functioning adult person. Heck–happiness is subjective, but that doesn’t mean we can’t try to quantify it, track it, and figure out how to manipulate it in ways that work for us.

Of course, there are a million lifestyle and self-help books out there that talk about “optimization,” and critics of this concept have justifiably maligned it as a fake, oppressive, and ultimately impossible ideal. And I absolutely agree that the perfect should not be the enemy of the good. However, when we are so intimidated by the idea of perfecting or optimizing our lives that we don’t even attempt to make decisions that improve them, aren’t we giving up on significant joy potential? It’s the same argument I (unsuccessfully) make to my friends who staunchly refuse to even make a New Year’s resolution, simply because they don’t believe they will be able to fully achieve it. Okay, sure, you may not become conversationally fluent in German in the next calendar year. But if you made a resolution and tried even for a little bit, you’ll probably be a little more conversationally fluent in German by the end of the calendar year than you would otherwise have been. And when it comes to happiness, doesn’t every little bit count?

If you want to try this for yourself, I say go for it. Grab an old notebook and start tracking. Even if you don’t do it every day or make it through a full year, it might provide some interesting insights just by making you take sixty seconds at the end of every day to reflect on how you spent your time and how that made you feel. And that’s at least a little bit better than waiting around for someone to build you a chocolate hot tub.

Leave a comment