Basically every unmarried person I know (and, actually, most of the married ones too) has cited the same source of dissatisfaction in their lives: their low quantity of close, genuine, satisfying relationships.

Establishing your adult life in your 20s and 30s means, for most people, living independently from their families for the first time and relying more heavily on friend relationships. Unfortunately, it is also a time when making and keeping friends is difficult, as we juggle full-time jobs and adult responsibilities that have yet to become second nature.

Feelings of social isolation among young adults are also more prevalent thanks to that catch-all cultural villain, social media (thank heavens for Facebook! If it didn’t exist, what would we blame all of our mental and emotional health problems on!).

I’ve had so many conversations with friends over the past few years about their discontent with the quantity and quality of adult friend relationships–and I’ve experienced similar dissatisfaction. I think it’s time we look inward and consider a few key questions:

In 2025 America, what do friends owe to one another? What do you need and expect out of your friend relationships, and do those needs and expectations align with what your friends are willing, able, and prepared to provide?

Understanding relationships as transactional

The idea of transactional relationships is instinctually off-putting to many, myself included. I don’t want to believe that I am only friends with someone because I need something from them, and a society driven primarily by quid pro quo makes me squeamish.

But, setting aside the negative connotations behind the word “transactional,” I think we have to consider what we put into and get out of relationships if our goal is to improve the quantity and quality of those relationships. Why would we want more friendships, unless those friendships added something positive to our lives? What is the nature of that positive addition, and what specifically about the friendship creates it? Until we answer that question, how could we know what to seek out in a friend?

Whether consciously or subconsciously, we all approach friendships with some expectation of the impact it will have on our lives. I might be bored, and want friendships that distract me and create opportunities to go new places and try new activities. I might be lonely, and want friendships that give me an outlet to share aspects of my life that were hitherto confined inward. I might be curious, and want friendships that invite new opinions, backgrounds, and points of view into my mindset.

If I keep my goal vague (“I want more friends, I want better friends, why don’t I have enough friends”) I will be completely in the dark when trying to make those new and better friends. I won’t know who to reach out to, and once I’ve made a connection, I’ll have no framework for judging the strength and positivity of that connection. For this reason, it’s important to codify your side of the friend transaction: what you need and expect from the people you’re close with.

It is equally important to understand their side. What are their needs and expectations, and are you prepared to meet them? Will meeting those expectations be natural and fulfilling for you, or will it be such an uphill battle that it counterbalances any positivity derived from the relationship?

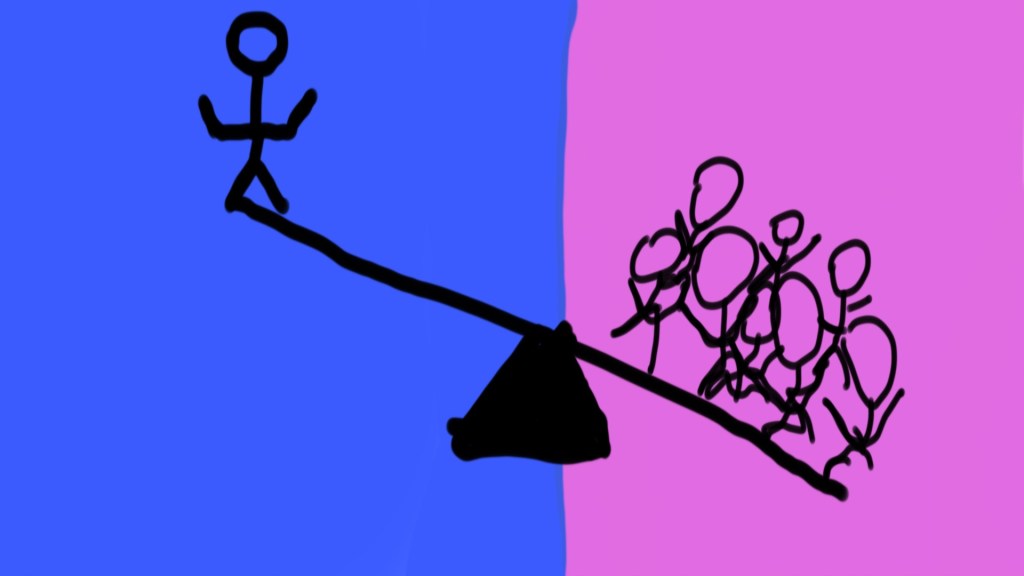

As I’ll discuss more in a second, the most straightforward path to maximizing the quantity and quality of your relationships is by aligning your expected output with their willing input–and vice versa. But before that alignment can occur, you need to understand both sets of expectations.

What happens when expectations are misaligned

Here’s an example. I believe that it’s important for my friends to closely listen to what I say, respond to those statements meaningfully in the moment, then remember and follow up on them later. The origin of this belief is not important (although it is interesting and very likely Freudian in nature). But because of this belief, I expend a lot of energy when interacting with my friends to ensure that I listen, respond accordingly, keep track of their projects and interests and life developments, and ask about them next time we meet. And also because of this belief, I feel a sense of letdown when my friends do not behave in that way toward me. When that expectation is not met, the relationship feels less close.

But in my experience, most people in their 20s, at least in our current global moment, would not rate that type of behavior as particularly important in close friendships. How do I know this? A) because I’ve asked, and B) because friends often react in surprise when I remember something they’ve said and ask about it later, as if they didn’t expect me to be paying that much attention. And C) if they thought that behavior was particularly important, I’m guessing they would exhibit it more frequently. Due to any number of factors–again, the purpose of this essay is not to diagnose the origin of the expectations but rather than codify and align them–my expectation for a close relationship does not match what most people expect to provide in a close relationship.

The result of that mismatch is twofold: I feel disappointed and let down by my friends for not behaving the way I expect, and although my behavior might strike them as unexpectedly pleasant, it is not crucial behavior integral to them feeling close to me. It’s not a bad way to act. But it’s not the way they need me to act, and as we’ll discuss in a moment, it might actually be directing my energy away from the behaviors they do need and expect.

Here’s an example going the opposite way. Now, bear with me here, because this statement may initially seem a bit sociopathic…but at heart, I don’t believe that “the truth” is something I owe to others in order to have a close relationship with them. I’m a big believer in pretty much any form of lying, big or small, if it facilitates the ease of an interaction. It’s my biggest red flag.

So, up until very recently, I did not prioritize authenticity in my interactions with my friends. I didn’t think it was a bad thing to be authentic, per se, it’s just not something I need or expect from others, and I didn’t think about how they might need and expect it from me. Yet, as I’ve been informed in no uncertain terms, most people do view this as a requirement of close relationships, and will consciously or subconsciously distance themselves from a friend if they sense a lack of authenticity.

There I was, exerting a ton of energy and care into listening closely to what they said, responding in a meaningful and insightful way, remembering tiny details about their lives, and asking about them later…all things that were nice but that they didn’t prize as highly as authenticity, while I neglected to be authentic and truthful: something they did require from me in order to maintain closeness.

Nice-to-haves are not must-haves

We see here the difference between nice-to-haves and must-haves in a relationship. Most things you put into a friendship are good and positive and the person, if asked, would rather have them than not have them. But there’s a big difference between those nice-to-haves, and the core expectations and requirements that dictate the closeness of the relationship. With only nice-to-haves, a person can be fun to hang out with and a good casual friend. But only with the must-haves can the relationship be close, satisfying, and long-lasting.

I know a few people who have, to my eye, a lot of friends. A veritable posse of pals. And I’ve been surprised when they’ve indicated the same dissatisfaction with the quantity and quality of their close relationships as my more traditionally loner friends feel. I think this is because they are pleasant to be around, and attract a lot of people with a lot of nice-to-haves–but because not enough of their relationships are truly meeting their needs, they are just as lonely.

To return to my personal examples: should I STOP listening closely to my friends and asking about things they’ve mentioned in the past? Of course not! But with every choice about what to put into a friendship, there is an opportunity cost. It takes a high level of energy for me to have what I deem to be a “successful” friend interaction. Close listening for long stretches of time can be hard work, frankly, and it takes mental energy to log small details, call them readily to mind later, ask thought-provoking questions, and make sure my facial expressions and body language match appropriately with what they are telling me.

Because this process is so draining, I am extremely socially flaky (my second reddest flag–we’ve shifted from scarlet to, like, a strong burgundy). I cancel plans at the slightest provocation. And until recently, I didn’t think much of it. But upon reflection and discussion with friends about what they valued most in close relationships, I realized that my flakiness was actually hurting the relationship more than my close listening was helping the relationship. I was providing a nice-to-have, but in so doing was less often providing the must-have of consistent and reliable physical presence.

The conclusion here? If it’s a person you want a closer relationship with, make sure you are providing the must-haves first. Then, with your leftover time and energy, you can dip into the nice-to-haves.

There are societal and cultural trends in relationship expectations

These personal examples are, of course, personal. And I think it’s true that, to a certain extent, everyone has their own set of priorities and expectations in terms of close relationships with their friends. But there are certainly sociocultural trends and norms that most people adhere to most of the time.

If I were to ask one hundred people to list their must-haves in order of must-ness, there would be differences in the priority order and the specific group of traits listed. But across the population, I think a majority of people would list pretty similar mandatories based on their stage in life, the values reflected across broader society at the current moment, the relationships they see depicted in popular media, and other factors that impact a society rather than just an individual.

To sling some additional mud at Zuckerberg and Co.: I expect that a few decades ago, more people would list “close listening, memory, and follow-up” as a must-have, just like I do. But I think the overall degradation in attention spans and ability to focus has made this so difficult for so many people that they simply do not exert effort to achieve it in their personal lives–and have come not to expect it from others, either.

When thinking about expectations alignment, you need to think not only about a 1:1 relationship (“does my specific set of needs and expectations match what this other person is willing and able to provide”) but also about global trends (“do my needs and expectations align with most other people’s at this time?”) If not, that’s okay–but you’re going to have a harder time making and maintaining close relationships, since you are compatible with a smaller portion of the population.

It’s not you, it’s me

So, you’ve done some soul searching. Perhaps you’ve taken an online quiz. You’ve realized that what you long suspected is true after all: you’re a weirdo, and your relationship expectations do not align with many of your friends or with society writ large.

What should you do about it?

If you are content with the quantity of your close relationships, you don’t have to do a darn thing! You don’t even need to read the rest of this essay. Heck, you didn’t need to read the first part of this essay, so stew on that opportunity cost for a second.

Plenty of people are content with only a few close relationships, and to that I say, godspeed. If you’ve found a few people who meet your needs and whose needs you can satisfyingly meet, just maintain those relationships without adjusting any expectations. But make sure that you are not mistaking time spent with someone with true closeness. It may be that you have only a few friends, but think you’re emotionally all set because you hang out with them every day. In non-academic circles, this is referred to as “that stereotypical teenage boy friendship where they play a ton of video games together without speaking.”

Using the expectations framework described above, evaluate those relationships to ensure they are meeting your needs, you are meeting theirs, and the relationship adds real value and satisfaction to your life. If not, it might be time to seek new ones.

If, like many others, you actively want more close relationships, there are a few things you can do:

#1: Talk to your friends explicitly about your must-haves

This is a terrible prospect, at least for me. An outward discussion of the transactional nature of our relationship, coupled with an implicit criticism that they haven’t been meeting my needs up till now? I’d literally rather die.

But thanks to our contemporary pro-therapy, air-out-all-the-dirty-laundry culture, this has gotten easier in the past decade or so. I have found ways to have interesting and productive conversations with my friends, during which I explain to them the things I value in a relationship and ask them what they value in return. Once I have greater clarity about those expectations, I have been able to modify my behavior accordingly and achieve greater closeness.

#2: Consciously adjust your expectations to better match the majority’s

Our must-haves don’t come from nowhere–they probably come to us via the same route as our values and ethics: a blend of nature and nurture with a healthy pinch of intentional decision-making. And like our values and ethics, they are, to a certain extent, changeable.

If you’ve noticed substantial differences between what you expect from others, and what a majority of people expect to provide, work on changing your expectations. I see two main ways to do this.

First, take time to intentionally consider what they are providing you and the benefits thereof. For example, people sharing deep feelings and emotions with me is by no means one of my natural must-haves, but I think it is for a large majority of other people in our current global moment. By noticing when people do that with me, and reflecting on the warmth I feel as a result and the insights I glean about the world around me based on their experiences, I can intentionally increase my appreciation for that nice-to-have. And with enough intentional appreciation, a nice-to-have can become a must-have.

The second method is to seek non-friendship methods for meeting your needs. If people listening closely and asking follow-up questions is a must-have that your group of friends isn’t meeting, seek professional help! Find a therapist, or start journaling, or leverage other relationships (like your mom–thanks for reading, Mom!) to meet that need. When the need is met in other ways, you’ll experience less dissatisfaction when your friends fail to provide it, and that frees up emotional bandwidth to appreciate what they do provide.

And of course, along with adjusting your expectations, adjust your behavior to better match what most other people expect and require from you. That will make you compatible with a greater proportion of society, increasing your opportunities to develop new close relationships. As long as their must-haves are not especially arduous for you to provide, or violate some ethical principle, spend your energy providing them rather than whatever you initially deemed was important.

#3: Forgo reciprocity

This one may stick in some people’s maws. But two separate objects can become closer even if only one of those objects moves. We paint an idealized picture of relationships where everything is perfectly reciprocal, and everyone puts in equal effort and reaps an equal reward…but that balance is not a requirement.

The first strategy outlined above requires explicit conversations with your friends, where you tell them what you need from them. But if you know what they need from you, you don’t necessarily have to tell them what you need from them. You can just work on better meeting their needs, and greater closeness will result. The downside, of course, is that you may resent them for all the work you’re putting into the relationship when they are still not meeting your needs. But if your overall need to feel closer to people supercedes your specific, relationship-based need about what that friend should be doing for you, it may be a sacrifice you’re willing to make.

It’s like love languages, but less cringe-y

This concept about understanding and aligning what we give and get from relationships is by no means groundbreaking. These terms–meeting needs, finding people you’re compatible with, and intentionally lowering or adjusting your standards–are often used when talking about romantic relationships. The supremely silly “love languages” trend is basically the Buzzfeed version of this concept.

There’s no reason that ideas we’ve accepted when it comes to romantic relationships can’t be applied to platonic friendships. And rather than the love languages, which are generic and limiting, this exercise forces you to codify the specific and unique factors that are important to you in platonic friendships, which is a category of relationship that is of utmost importance and yet often overlooked.

We all have to make sacrifices to be part of society. If we want friends, parts of ourselves have to change. That’s not a scary or an evil thing–and it is not a denial of your “true authentic self,” or whatever a middle school coming-of-age book might have you believe. What I am suggesting is simply a recognition of needs–yours and others’–and adjusting your behavior and thought patterns to maximize the opportunity that those needs are met.

Or you can go befriend ChatGPT, which needs nothing at all other than your soul!

Leave a comment